On 29 April 1970, over 50,000 American and South Vietnamese troops invaded Cambodia. The Cambodian Incursion, as President Nixon preferred to call the invasion, marked a new phase in the Vietnam War and the beginning of the war for Cambodia. That war would end five years later with the triumph of the communist Khmer Rouge.

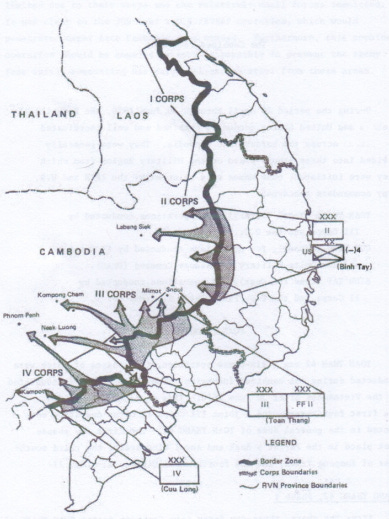

In one of the two main prongs of the attack, the ARVN 5th and 25th Infantry Divisions from III Corps and the 9th Infantry Division from IV Corps pinched off North Vietnamese bastions long established in a piece of Cambodian real-estate known as the 'Parrots Beak.' In another Cambodian protuberance called the 'Fish Hook', the American 1st Cavalry Division (less one brigade) advanced against North Vietnamese positions believed to house the Committee for South Vietnam (COSVN), the headquarters through which North Vietnam prosecuted the war against South Vietnam. Here the Americans inflicted heavy losses upon the NVA 7th Division and destroyed several massive stockpiles of equipment, including 6,100 individual and 900 crew served weapons in 350 separate caches.

To the North, the American 25th Infantry Division, the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division, and the ARVN Airborne Brigade made several forays across the border. Most impressively the 2/1 Cavalry found a huge arms cache they nicknamed 'The City'. Further operations by the 2/1 Cavalry uncovered another mammoth communist depot they nicknamed 'Rock Island East' after the famous American arms depot in Illinois. Near the border with Laos three divisions, the American 4th as well as the ARVN 22nd and 23rd, advanced against communist positions there, capturing several small depots. For example, the 4th Infantry Division uncovered a supply depot housing 500 tons of rice and a fully equipped hospital, and seized smaller quantities of individual and crew serve weapons. To the south, on 9 May, a taskforce comprising the American 1st Marine Brigade and the ARVN 9th and 21st Infantry Divisions cleared out NVA positions on the banks of the Mekong River. The task force entered Phnom Pehn two days later.

The Cambodian Incursion was more than just a military operation. It was a public relations move meant to demonstrate the growing capabilities of the South Vietnamese. ARVN forces were indeed proving they could fight and defeat the NVA. The three ARVN divisions in the 'Fish Hook' were divided into three task forces, 318, 333, and 225. Each task force was organized into a combined infantry-army group supplemented by an armored squadron and ranger battalion. After clearing out the 'Fish Hook' each task force pivoted west. Their goal was the city of Kompong Cham, then besieged by the NVA. Task Forces 318 and 333 advanced northwest along Route 7 while Task Force 225 protected the southern flank. They were in continuous contact with elements of the NVA 9th Division. Toward the end of the week NVA resistance stiffened in defense of their big base at the Chup Rubber plantation, on the Mekong just east of Kompong Cham. In two days of fighting more than 100 NVA were killed. Chup Plantation was taken by Taskforce 318 after a week long struggle. Taskforce 333 then pushed on and relieved Kompong Cham.

In total, the joint US/ARVN Cambodian Incursion inflicted more than 15,000 casualties upon the North Vietnamese and captured an immense amount of equipment including more than 22,000 individual weapons, 2,500 crew served weapons, 83,000 pounds of explosives and more than a million pages of communist documents. American and South Vietnamese losses amounted to 976 dead and 4543 wounded. Over two thirds of the casualties were suffered by the South Vietnamese, showing that they were taking on and bearing a greater burden of the war.

Nixon

President Nixon felt he had several good reasons for invading Cambodia. He believed the new pro-American government led by Lon Nol was weak and would not be able to hold on against the North Vietnamese. If Cambodia fell it would be another communist victory and Nixon could not personally tolerate that. He needed to look tough, both to the Soviets, and to the North Vietnamese, who gave no ground whatsoever in the Paris Peace Talks. An invasion of Cambodia could save that nation from the communists, bolster Nixon's world standing, and put immense pressure on Hanoi.

The idea of a Cambodia incursion had considerable support within the administration. Both General Creighton Abrams, commander of Military Assistance Command Vietnam, and Admiral John S. McCain, Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet, felt an invasion of Cambodia was sensible and feasible. The latter told Nixon so in a meeting held in Hawaii on 19 April. General Abrams had been toying with the idea of an invasion since the spring of 1969. He viewed the North Vietnamese presence there, and occasional cross-border attacks as a provocation that must be met. Ellsworth Bunker, the American Ambassador to South Vietnam, believed destroying communist sanctuaries in the country to be absolutely essential to Nixon's policy of 'Vietnamization'.

Vietnamization was the process by which the Army of the Republic of Vietnam gradually took control of the war. It was also the centerpiece of the Nixon Doctrine. Briefly, Nixon sought to remain involved in Southeast Asia, providing diplomatic support and military aid to America's allies, but with a much smaller American military footprint. Indeed, Nixon planned to withdrawal 150,000 American troops from Vietnam in 1970. An invasion of Cambodia led by ARVN troops would show the world that 'Vietnamization', the 'Nixon Doctrine', and Nixon himself were succeeding. After the Hawaii meeting with Admiral McCain, Nixon told Henry Kissinger, his National Security Advisor and closest confidant, 'This is what we've been waiting for.'

Nixon was also concerned that if he did not act soon Lon Nol’s government would fall and be replaced by a North Vietnamese puppet government. 'This may make it impossible to close Sihanoukville or to launch later air attacks on sanctuaries,' the president jotted in his notes. 'Time running out...' While he believed there were great inherent risks in an invasion, including provoking an NVA attack on Phnom Penh, a cessation of peace talks, and discord at home, Nixon believed the rewards outweighed the risks. He noted that these included diverting the communists from Phnom Penh, eroding the Cambodian sanctuaries, hurting North Vietnamese prestige and pressuring them to negotiate.

While Abrams, McCain and Kissinger favored the invasion, other elements within the administration were deeply skeptical. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird was adamant that US forces should not participate in the attack. Secretary of State William Rogers also opposed the inclusion of American troops. He argued that involving American troops, with the resultant domestic and international outrage and casualties was a 'high risk, low gain' proposition. He also doubted they could ever find and destroy COSVN. 'The damn thing moves all the time. We'll never get it,' he wrote. Hesitancy on the part of Laird and Rogers further marginalized them in a White House already dominated by Kissinger, cutting the president off from views other than the national security advisor's, and his own. On the eve of the invasion, four young aids on Kissinger's own staff, including Clinton era National Security Advisor Anthony Lake, resigned in disgust.

On 30 April, 1970 President Nixon went before the nation to justify the Cambodian Incursion. He described in great detail the NVA infrastructure within Cambodia and argued it was a great threat to American troops in South Vietnam. He claimed the communists had stepped up their guerilla activities out of these sanctuaries and were staging forces within for a large scale effort against South Vietnam. He also talked about the South Vietnamese forces participating in the incursion, pointing out that they were fighting on their own under South Vietnamese command. In the speech he argued that the communist world was daring the United States to act. Nixon seemed to take it personally. He said, 'It is not our power but our will and character that is being tested tonight. The question all Americans must ask and answer tonight is this: does the richest and strongest nation in the history of the world have the character to meet a direct challenge by a group which rejects every effort to win a just peace, ignores our warning, tramples on solemn agreements, violates the neutrality of an unarmed people, and uses our prisoners as hostages?'

Cambodia in 1970

Cambodia is the homeland of the Khmers. In 1970 about seven million people lived there, about half a million of these were ethnic Vietnamese. A further three quarters of a million Khmers lived in Vietnam and Thailand. Ninety percent of the population was rural. Phnom Penh, numbering 600,000 people, was the largest city, and the nation's political and cultural hub. Due to the legacy of colonization the city had a decidedly French feel. Cambodia is overwhelmingly low lying and tropical, with a pair of mountain ranges, the Cardamom and Elephant, in the southwest. Its most important rivers are the Mekong in the east, and the Tonle Sap in the west, both of which converge at Phnom Penh. Urban Cambodia, meaning Phnom Penh and a few other places like Kompang Cham and Kompong Speu, lived in a world apart from rural Cambodia. While urban areas were highly westernized, the vast majority of the country existed in a near primitive state with no electricity, few roads and little government. Most spoke only Khmer and had no knowledge of even rudimentary aspects of modern life such as electricity, plumbing and even clocks. The average Khmer farmer owned his land, but was deeply in debt to local money lenders, making them highly amenable to the communist message.

In 1970 the Khmer Rouge occupied the northeastern provinces of Kratti and Ratanakiri. At this time it was a small, extremely secretive organization numbering a few thousand soldiers at most. Here the Khmer Rouge had waged a low-level civil war against the government, carving out their own safe haven in which they could consolidate power and grow. The Khmer Rouge was led by the infamous Pol Pot, who like the rest of the leadership, had attended university in Paris where he became a communist in the Stalinist mode. The Khmer Rouge's Stalinism lead itself to almost comical paranoia. The party did not even admit it existed until 1977, two years after it seized power. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge hated the government and the West of course, but were also extremely distrustful of the North Vietnamese, whom they suspected of trying to subvert the Khmer Rouge.

Since 1941, Cambodia had been ruled by Prince Sihanouk. the prince fancied himself a renaissance man, dabbling in music, literature and other artistic pursuits. He ruled Cambodia as his personal fiefdom, dolling out important posts to his family or political cronies, who of course skimmed as much off the top of their budgets as they could get away with. Patronage and favoritism where Sihanouk's guiding principles; other than himself. He had served the French colonials, and later the Japanese. Sihanouk had maintained the nation as an 'island of peace', in his words, claiming neutrality. In the 1960s he had even broken off diplomatic relations with the United States.

In March of 1970, while receiving medical treatment in France, Sihanouk was overthrown by a military coup led by his prime minister, General Lon Nol, and his cousin, Prince Sirik Matak. Lon Nol declared the monarchy to be at an end and renamed the country the Khmer Republic. The coup was met with approval by Cambodia's middle class, who resented Sihanouk's corruption, but with rage in the countryside, where the peasants viewed the overthrow of the Prince as an act of blasphemy. This division, on top of the natural urban/rural divide would be important later in the war.

Lon Nol was pro-American and immediately demanded the exit of all North Vietnamese troops from Cambodia. He also staged anti-communist protests in Phnom Penh and unleashed a pogrom of anti-Vietnamese riots throughout the nation. In return for his anti-communist stance Lon Nol expected massive help from the Nixon Administration. He appealed for that help almost immediately, first, through Cambodian air force officers meeting with the American military attaché in Phnom Penh and later in an impassioned radio address given on 14 April, calling for American and international assistance against the communists.

The North Vietnamese in Cambodia

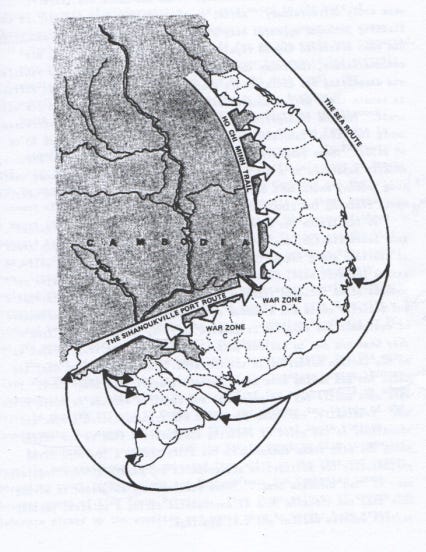

The North Vietnamese maintained a massive presence in eastern Cambodia. The elusive COSVN headquarters was located on the Cambodian/South Vietnamese border, and the infamous Ho-Chi-Minh trail ran through the country into South Vietnam. But the communist footprint in Cambodia amounted to much more. The trail was operated by the North Vietnamese 559th Transportation Group, a unit of 50,000 men consisting of transportation, engineering, anti-aircraft, signal, and medical personnel. The 559th was supported by a further 100,000 civilian laborers. A second route ran from the border back to the port of Sihanoukville. The communists considered this the safest conduit for supplies, as it was not subject to bombing or cross-border raids. The NVA openly moved supplies via the Sihanoukville route using a Cambodian civilian trucking company.

Supplies from both routes were stockpiled in NVA base areas along the border. These were crucial to COSVN's conduct of the war. They served as divisional headquarters, supply depots, barracks and hospitals. There were dozens along the border. Base Area 609, in the triangle of the Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian borders, opposite the northern province of Kontum, was the most important, serving as the main distribution node for supplies further south. In all there were six regular NVA divisions in Cambodia.

After Lon Nol's ultimatum, the North Vietnamese turned their guns on the Khmer Republic. The Cambodian army, the Forces Armee Nationale Khmer was in no way prepared to meet the professional and battle hardened NVA. The country was divided into six military regions plus the Phnom Penh Special Military Zone, each with a general commanding. The army numbered twelve brigades, 32,000 men in total. These were badly armed, trained and led. Of FANK's 60 battalions, more than 2/3rds were concentrated in Phnom Penh, the southeast border or the northeast. The air force had only 1250 men and one airbase, Pochentong outside of Phnom Penh.

The NVA offensive began on 29 March and easily swept aside FANK. Wrote one Cambodian general, 'From the very first days, therefore, the FANK was driven back by the enemy push.' Within days the NVA pushed FANK up against the Mekong and Tonle Sap Rivers in the east, while in the south the NVA established footholds in the west and southwest of Phnom Penh.

Operation Menu

In his Cambodia speech, President Nixon said that up until the incursion, the United States had 'scrupulously respected' that nation's neutrality. This was a lie. It was in fact the worst lie told by an administration that lied as a matter of course. Since March of 1969 the United States Air Force had carried out a sustained aerial campaign inside Cambodia called Operation Menu the umbrella name for a slew of air raids. The first of these had been launched on 17 March against the 'Fishhook'. The raid was in fact not Nixon's idea but General Abrams’, who requested the strike in the hopes of catching COSVN headquarters. Before him, General William Westmoreland had also requested B-52 raids in Cambodia.

The first series of strikes carried out under the Menu umbrella, called Operation Breakfast, were carried out against communist base area 353 by B-52 Bombers out of Anderson Air Force Base in Guam. As the operation grew, other strikes were launched out of Okinawa and Thailand. B-52s out of Guam flew five hours across the Pacific and were picked up by ground radar stations in South Vietnam which guided them to the target area via a radar tight beam. In an 'Arclight' strike, as they were called, a single B-52 could create a carpet of destruction five hundred meters wide and 1500 meters long.

Over fourteen months Operation Menu expanded to include five sub-operations. In addition to Breakfast there were operations Lunch, Snack, Dinner, Dessert; each directed against a specific communist base area. In all 3875 sorties, dropping 108,823 tons of bombs were carried out during Operation Menu. While the original strike was uncovered by The New York Times, the Nixon Administration henceforth went to extraordinary measures, including falsifying the formal mission reports, to keep further operations secret.

Operation Freedom Deal

Operation Menu ended in the spring of 1970, but this was not the end of American bombing in Cambodia. On 19 May, 1970 the Nixon administration undertook a massive aerial campaign called Operation Freedom Deal. Carried out by the 7th Air Force in South Vietnam and B-52s out of Guam, Freedom Deal was a massive attack against communists in Cambodia. Until banned by law beginning on 15 August 1973, the US Air Force dropped thousands of tons of ordnance on Cambodia per month. A myriad of aircraft were used in addition to B-52s, including F-4 Phantoms, F-105 Thunderchiefs, prop engine A-1 Sky Raiders, and A-119 Spectre Gunships. The Seventh Air Force attacked troop concentrations, supply depots, staging areas, and lent desperately needed combat air support to FANK. For example, in April and March of 1972 B-52s hit the NVA 1st Division then operating in eastern Cambodia. In November and December of that same year, B-52s struck communist troop concentrations on Route-5, west of Phnom Penh. In support of these Arclight strikes, Marine A-6 Intruders flew night missions, while American Spectre and helicopter gunships were called in to lend tactical air support to Cambodian troops.

While Operation Freedom Deal was certainly a tactical and operational success, it was a long-term disaster for Lon Nol's government and the best recruiting tool at the Khmer Rouge's disposal. B-52 strikes cut swaths of destruction through communist bases and villages alike. In many instances fire control officers called in B-52 strikes against village meetings, thinking they were communist rallies. Khmer Rouge officers often took civilians through bombed out areas showing the damage Lon Nol's government had allowed the Americans to inflict. In a meeting with Nixon, Kissinger told Nixon, 'The problem is, Mr. President, the Air Force is designed to fight an air battle against the Soviet Union. They are not designed for this war...'

Early in the war, the American Embassy in Phnom Penh served as the conduit through which airstrikes were launched. FANK commanders would request a strike, this request would be sent to the American embassy where a small staff would then relay it to the 7th Air Force. As the war went on the air force attaches in the embassy became more deeply involved, reviewing air support requests, and screening strikes. Eventually the air support operation was moved out of the embassy into a special office in FANK headquarters, and FANK units received their own radios for calling in airstrikes. The first tactical airstrikes, originally called Operation Patio, were limited to a depth of 28.8 miles inside Cambodia. Of course the 28.8 mile limit was often violated, both intentionally and unintentionally and then lifted all together. American air power became a dominant feature of the war, and crucial to Lon Nol's government. The aerial campaign was massive and around the clock.

Arming FANK

An integral part of the Nixon Doctrine was arming indigenous militaries to fight Washington's enemies. As such, in 1970 President Nixon asked for and received a grant of $185 million from Congress for the expansion of FANK. In June of 1971 the administration, on Kissinger's advice, expanded the aid program and received from Congress a new appropriation for $275 million. In an internal memo to a White House policy group, Kissinger defined the administration's three point policy: keep the anti-communist Lon Nol in power, arm FANK, and urge the government to go on the offensive and get the NVA out of Cambodia.

The expansion program was actually quite successful. By the end of 1972 FANK grew to a paper strength of 220,000 men in four American style divisions plus one airborne and one armored brigade. The air force expanded too, numbering 154 aircraft. The navy grew from a mere seven vessels in 1970 to 123 by 1973; most of these were river patrol craft.

Like the aerial campaign the aid program was run out of the American embassy. Here the Military Equipment Delivery Team reported on the arming of FANK and made recommendations to Washington. These recommendations usually included requests for more aid, which required more MEDTC personnel. MEDTC was commanded by General Theodore Mataxis, a veteran of WWII, Korea, and Vietnam, who had recently commanded the 23rd Americal Division. He was a blunt man who disdained the Cambodians and the diplomatic staff in Phnom Penh. Mataxis personally reorganized FANK's logistics system, even going so far as to import Filipino workers who were familiar with the American way of doing things. He also feuded with the civilian diplomatic staff who were trying to maintain, on the administration's instructions, a low profile. In 1971 Mataxis requested and received more military personnel. MEDTC officers, who were supposed to supervise distribution and verify 'end use' in the field often took a more active role and became de facto combat advisors in defiance of US Law.

By late summer of 1970, Lon Nol felt FANK was ready to take the offensive. There followed operations, Chenla I and Chenla II. Chenla I was an effort to clear Route-7 and Route 21 and relieve the besieged town of Kompong Thmar. Twelve FANK battalions attacked in two columns, but these controlled no more than the territory in their immediate vicinity. FANK operations were bogged down by NVA roadblocks and mortar barrages. When FANK columns were able to advance, NVA forces simply slipped back in behind them. In October of 1971, Lon Nol tried again. Chenla II sought to open up Route-7 North of the Mekong and relive Kompong Cham. Like its predecessor, Chenla II failed. Once more FANK troops were able to advance up the highway, but unable to hold territory they took. Each garrison left behind was overrun by the NVA.

The Chenla offensives showed the United States could arm FANK, but not turn it into an effective army. In South Vietnam American military equipment came with American military advisors, who trained the rank and file, but more importantly, instructed junior officers in the art of leadership and command. As noted above, South Vietnamese forces proved capable in the Cambodian Incursion. Combined with American advisors and airpower, there is no reason why FANK could not have become an effective fighting force as well. That said, US law prevented the Nixon administration from providing those crucial advisors. FANK would continue to be a well armed force, largely incapable of fighting a modern war.

1973: The Khmer Rouge Comes Out

For the first three years of the conflict, the war pitted Lon Nol's government against the NVA. In January 1973, the NVA withdrew. This was the Khmer Rouge’s time. For years they had hunkered down in the northeastern provinces building an army. That army was comprised of thirteen divisions, most numbering between four and six thousand men. The typical KR division was divided into three regiments each of three battalions. KR divisions had few heavy artillery pieces but a myriad of man-portable mortars enabling quick frontline battlefield support. They were essentially light divisions, capable of quick movement, but as will be seen, at a severe disadvantage against entrenched forces. On orders from Pol Pot and his Marxist adherents, the Khmer Rouge would launch a grand dry season offensive aimed at taking Phnom Penh and ending the war.

Against the coming offensive FANK had two lifelines it had to defend at all costs. The first of these was Pochentong airport, west of Phnom Penh. The second was the Mekong River. American supplies came through these conduits and without them Lon Nol's government was doomed. While most of the countryside in south and eastern Cambodia was under communist control, the urban areas remained in government hands.

The first Khmer Rouge attacks fell on Kompong Thom, FANK positions astride Rt-1 along the Mekong and the river town of Neak Long. If Neak Long fell the Khmer Rouge could block the Mekong. While the Khmer Rouge did gain ground here, FANK counterattacks combined with naval and air support retook most lost positions. In February, the Khmer Rouge renewed these efforts and also launched attacks against Rt-2 and Rt-3, west of Kompong Cham in an attempt to isolate the city. Once more FANK lost ground but was able to retake it with massive American air support. When these failed the Khmer Rouge shifted attacks further south, again FANK held out and counterattacked. Time and again Khmer Rouge efforts on the Mekong were thwarted by preemptive airstrikes along the river banks. Escorting F-4s and A-7s also provided crucial support.

Having failed utterly to cut the Mekong lifeline, in July the Khmer Rouge shifted its efforts once again. This time they launched a direct assault on Phnom Penh, attacking defenses west and south of the city. Throughout July fighting raged along the rail line and a few towns held by FANK 3rd Division and along the Prek Thnaot river held by FANK 7th Division. Once more FANK was pushed back but did not break. The outer defenses had been lost, but thanks to FANK firepower and massive American air support the inner line held. Throughout the 1973 dry season offensive, B-52s hammered Khmer Rouge positions. These strikes also hardened Khmer Rouge resolve and turned Cambodian opinion against the government. In one horrific accident, a flight of three B-52s accidently bombed the town of Neak Luong, killing 137 and wounding a further 268. By U.S. law, that air support ended on 15 August 1973. FANK would now have to hold off the Khmer Rouge on its own.

End of Bombing

American bombing was not only crucial to the war effort, it was a central part in Nixon's negotiating strategy in Paris. While Kissinger was able to reach a peace deal with the North Vietnamese, he was unable to include Cambodia in the bargain. The administration was convinced that Hanoi controlled the Khmer Rouge and could be persuaded to rein them in for a peace deal in Cambodia. In fact the North Vietnamese had very little control of the Khmer Rouge, who deeply distrusted Hanoi, partly due to their ingrained and natural paranoia and partly due to historical animosity between the two nations. Relations were so bad that fighting periodically broke out between Khmer Rouge and NVA troops. In the final Paris Peace Accord, Kissinger was able to include language about a mutual ceasefire in Cambodia. Lon Nol did call for a ceasefire, but he was ignored by the Khmer Rouge.

The American bombing may have stopped in 1973, but the flow of supplies through Pochentong Airport and up the Mekong River continued. MEDTC, now under the command of General John Cleland oversaw the delivery of replacement equipment. Without a doubt the most important item coming up the Mekong was ammunition which FANK used at a prodigious rate. Cleland's reasoning was simple. 'The FANK depend on firepower to win. Seldom has FANK outmaneuvered the enemy - he has outgunned him.' By the middle of the year, 87% of the supplies going to FANK was ammunition.

Despite the failure of the 1973 dry season offensive, the Khmer Rouge launched another such attack in January of 1974. Once more the Khmer Rouge attacked FANK positions west of Phnom Penh. Even so FANK held out and repulsed the Khmer Rouge killing more than 300 in five days of fighting. All month the Khmer Rouge probed FANK defenses but failed to breakthrough anywhere. In these battles FANK hit upon an effective tactic. When counterattacking, local commanders called upon squadrons of M-113 tracks to lead the way. While these may sound like a feeble armored element by western standards, to Khmer Rouge peasant soldiers, massed M-113s were terrifying.

After the failure of the Phnom Penh attack, the Khmer Rouge shifted once more, this time to Cambodia's second cities. Fierce fighting ensued for the city of Oudong, an important religious and nationalist symbol in Cambodian culture. Here the battle followed the same pattern as around Phnom Penh, with the Khmer Rouge taking ground only to be beaten back by FANK counterattacks. The Khmer Rouge eventually took Oudong in late March. Lon Nol ordered that the city be retaken at all costs. FANK Was unable to do so until August. FANK and the Khmer Rouge fought similar battles for the nation's mid-sized cities to the east and south of the capitol. At Sihanuakville, FANK troops bloodily repulsed Khmer Rouge assaults, as the navy was able to keep them resupplied. FANK forces advancing behind squadrons of M-113 relieved Kompong Luong, which had been besieged by the Khmer Rouge.

Given that FANK was holding its own, even without American airpower, in 1974 one could argue the Nixon Doctrine was working. In April of 1974 Nixon sent a new ambassador to Cambodia, John Gunther Dean. Unlike his predecessors, Dean was a veteran of the region, having served in the embassy in Laos, where he helped forestall a military coup and build a coalition government. He was an active ambassador. Upon arriving in Cambodia, Dean toured the country. He closely supervised the distribution of American aid and flew to battle zones exhorting Cambodian commanders. After his initial tour, Dean suggested to Kissinger that he contact Khmer leadership, one of its members was then touring North Africa. At this stage the Nixon Administration was deep into the Watergate scandal and congressional investigators were uncovering not just the secret of Operation Menu, but the scope of Nixon's cover up.

While Nixon's hold on the White House was steadily whittled away, the American aid program to Cambodia greatly expanded that nation's armed forces. By the beginning of 1974, FANK numbered four infantry divisions, each of three infantry brigades, plus an independent armored, airborne and artillery brigade, all told an army of 202,000 men, at least on paper. Despite Ambassador Dean's attention and the micro-management of the MEDTC teams, most officers greatly misrepresented the number of troops on roll and pocketed the money paid to these phantom soldiers. That said, FANK troops going into battle were impressively armed. The average Khmer soldier walked onto the battlefield wearing an American uniform, helmet, belt and boots. He carried an American made M-16. He could count on ready fire support from American M-30 and M-50 machineguns, 60 and 81mm mortars, and squad mates armed with American M-79 grenade launchers. His divisional artillery units were armed with American 105 MM howitzers. In the New Year, Lon Nol relieved FANK's commander and replaced him with General Sak Sutsakahn. He described the situation he inherited thusly 'the general situation throughout Cambodia consisted of little more than defeats everywhere.' He blamed poor training, supply shortages and systemic corruption. Cambodian units were indeed bringing an impressive array of firepower onto the battlefield, but in four years of fighting their commanders had learned little of the art of war.

On the other hand, by the beginning of 1975 the Khmer Rouge was showing it had learned much from the defeats of the previous two years. On New Year's Day they began a series of heavy rocket barrages on Route-One and mined the Mekong supply line, severely hampering Phnom Pehn's communications. This was accompanied by renewed efforts first against Phnom Pehn's northwest and later against the southeast. More importantly, in March the Khmer Rouge unleashed a massive assault on Neak Luong. To facilitate that assault, the Khmer Rouge smartly attacked Route One, North of the town. Facing assaults against its defenses and with its communications severed, Neak Long fell on 1 March. The Mekong supply route was permanently closed. Now Pochentong Airport was Phnom Pehn's only lifeline. This is where the next Khmer Rouge blow fell.

Nixon was six months resigned from the White House, but Kissinger remained to salvage his Cambodian policy. As such, Ford continued support for Lon Nol. In Phnom Pehn, Ambassador Dean pleaded with Kissinger to abandon Lon Nol in the hopes of forming a peace government with moderate elements in the Khmer Rouge. Instead he and President Gerald Ford pressed congress for more military and humanitarian aid. Congress was by this point deeply skeptical and declined to throw more money into the Cambodian sink hole. As the Khmer Rouge closed in on Phnom Pehn, Kissinger tried one last gambit, saying the United States would support the return of Prince Sihanouk. The Prince himself rejected Kissinger's plan. Besides, the Khmer Rouge knew total victory was a few days away. Finally, on 1 April Lon Nol resigned and left the country on his own. Kissinger was denied his best bargaining chip. On 12 April Ambassador Dean ordered the evacuation of the American embassy. On 15 April the Khmer Rouge finally overran Pochentong Airport. What remained of the government fled the city and the Khmer Rouge entered on 17 April.

Nixon is often criticized for 'widening the war,' but this is not true. The war was already in Cambodia. The nation only fell to the communists after the American congress withdrew aid to FANK. Had the Cambodians received continued material and air support, the war most likely would have dragged on. While not a great result, war would have been less bloody than the peace that followed the fall of Phnom Pehn. Within days of taking the capital the communists sacked the city and expelled its inhabitants to the countryside, where more than one third of the population, over two million people, would die.