Before the Second World War, the Indian Army numbered 82 independent battalions. When the Japanese attacked Burma these were hastily organized into higher echelon formations, brigades, and divisions. The typical brigade contained two Indian battalions and one British. Most of the armored and artillery battalions were British as well. Despite the colonial nature of the Indian army, thousands of native soldiers rose through the ranks, becoming officers, many battalions were in fact commanded by Indians. By the end of the war, there were two and half million men under arms organized into 16 divisions each of three brigades. Indian divisions fought with great distinction in North Africa, East Africa, Italy and the Far East.

So unlike many newly independent nations, India had a vast pool of trained soldiers and trained officers with which to build its new army. Actually, the Indian Army wasn’t built so much as it was turned over to the new government of India. Like the subcontinent, the army of India would have to be partitioned. This would be difficult as the British had wisely refrained from organizing units by religion. Most units, down to the squad level were a mix of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. That said, there were units that were majority Muslim and these would be transferred to the nascent Pakistani state. Even paperwork was divided, with large staffs sorting through reams of paper and dividing it into stacks relevant to Pakistan and India. Much of this process was overseen by British generals, men who had made their names in the long war for Burma. General Joseph Lentaigne, who had taken over Special Force after the death of Orde Wingate, was responsible for much of the staff work. The titular head of the Indian Army was General Sir Robert Lockhart a veteran administrative officer, while Pakistan’s first Army chief was General Frank Meservy (who commanded 7 India Division in Burma and later IV Corps).

When the final breakup and reorganization of the army was complete, Indian authorities retained the old British system. Divisions were comprised of three brigades, each of three battalions. Rather than erase its British past, the Indian Army embraced it. Indian units retained the traditions and battle honors earned during the British Raj. In most cases, names and designations, such as 8th Gurkhas or 1st Rajputs, were saved as well. On Independence Day, 15 August 1947, the Indian Army numbered 460,000 men. These were veteran, professional soldiers led by and large by a native officer corps which had been trained like British officers and emulated them in style and manner. In a few years, these Indian officers would be running the army. In addition to the commanders in chief listed above, more than 2,800 British officers stayed on to oversee the transition.

While the breakup of the army was relatively amicable, the partition of the country was anything but. Millions of Hindus and Muslims suddenly found themselves living on the wrong side of the border. A great mass migration in both directions began. Riots broke out and massacres ensued. In one notorious incident, a train bound for India from Pakistan arrived over the border with all its hundreds of passengers dead. There was also the issue of Kashmir, the northern state which lies between India and Pakistan. Though it had a Hindu Maharaja, who elected to join India, most of the population was Muslim. As such Pakistani President Ali Jinnah insisted Kashmir belonged to Pakistan. The new Indian President, the great Jawaharlal Nehru, refused to give in.

The issue went unresolved for many months when, in October of 1947, Pakistani raiders descended the mountains east of Kashmir and invaded the state. The force numbered about 5,000 Mashud tribal irregulars from the Northwest Frontier Province. They advanced quickly along Kashmir’s main road, scattering the few Indian units present, and sacking the towns they took along the way. Within a few days, the raiders were in central Kashmir and advancing down the Srinagar River Valley. They received help from Muslim soldiers they encountered along the way. While the incursion received little direct aid from Pakistan, President Jinnah and the military undoubtedly knew about the operation ahead of time and encouraged it. In a meeting with Lord Mountbatten (who was overseeing the Partition), Jinnah said that if the Indians withdrew from Kashmir, ‘I will call the whole thing off.’

To the south, Pakistani irregulars attacked the Jammu region of Kashmir in the hopes of cutting off Indian access to the province. In the process, they surrounded Punch in the north, Kotl in the center, and Mirpur in the south. The former was not relieved until late November after a grueling mountain valley campaign on the part of Indian 5 Brigade.

Nehru responded forcefully to the Pakistani challenge. He dispatched 1 Sikh Battalion to Kashmir with orders to stop the tribal advance. The battalion was flown into the town of Srinagar and immediately advanced up the Srinagar River Valley. After fighting a battle with Pakistani irregulars south of Baramular, 1 Sikh Battalion fell back to Srinagar proper. With the situation there stabilized, the Indian government poured reinforcements into Kashmir and neighboring Jammu. These included 50 Para Brigade, 161 Brigade, and 268 Brigade, units which had been in the thick of the fighting in Burma.

Indian high command planned a series of limited offensives meant to relive pressure in Jammu and retake territory lost to the Pakistanis. Over the course of November and December, Indian forces in Jammu launched a two pronged offensive with 50 Para and 268 Brigade gradually clearing the Pakistanis out of the Kotli area. Punch was relieved by a column of three battalions, which systematically drove the Pakistanis off the nearby heights and marched into town on 21 November. Even further south, Indian forces attacked and captured the Pakistani held town of Chamb, west of their staging area at Jammu, thus eliminating a threat to the Indian LOC.

There was constant skirmishing between opposing forces throughout the winter months of 1947-48. The Pakistanis were not idle. During the winter, thousands of so called Azad Kashmir volunteers were deployed to the area as were several battalions of Pakistani regulars. The Indians used the respite to consolidate their hold and plan the next phase of the war. By the time the snows melted, the Indians had two reinforced divisions in the region, the 19th based on Srinagar and the 26th in and around Jammu. More importantly, the Indian’s awkward command situation was resolved. Operations in Jammu and Kashmir had been overseen by British General Dudley Russell, who was forbidden by British authorities to visit the front. In January, at Russell’s suggestion, command passed to Lt. General K. M. Cariappa, a native Indian.

The 26th Infantry Division was given the task of retaking Domel and the important crossroad of Uri, about 50 miles to the northwest. The division advanced on a two brigade front and made good progress, pushing about 30 miles in five days against light resistance. Domel proper lay ahead. The 161 Brigade, consisting of four battalions, advanced in two prongs against increasingly stiff resistance as they tried to envelop Domel. The northern prong met its objectives, advancing over three miles, but the southern prong, after taking one Pakistani strong point along the line of march, ran out of steam and was unable to advance further. The division commander sent a battalion south and, after fighting several small engagements with Pakistan forces, it got around the enemy flank. But before the breakthrough could be exploited, the Nehru government agreed to a UN brokered ceasefire and ordered his commanders to halt operations.

Nehru agreed but the Pakistanis did not. The Pakistanis used the respite to gather several battalions of regulars and Azad Kasmiris along the front and launched a general offensive in mid-July. In the center, the attack fell on Tithwal at the head of the Srinagar Valley. This effort was bloodily repulsed by Indian 6 Rajputanana Rifles and fighting continued there well into November. In the north, the Pakistani attack fell on Skardu which was isolated, and eventually forced to capitulate, after which an orgy of murder and rape ensued. The fall of Skardu was particularly alarming as it opened up the entire valley to attack. Should the valley fall, the Indian position in the rest of Kashmir would be untenable. A Pakistani force was also advancing from the west up the Sonamarg Valley and had taken Kargil, mere miles from the Srinagar.

General Carippa rushed 77 Brigade to the eastern entrance of the Sonamarg valley, behind the Pakistani advance. Their first target was the enemy position at the mountain stronghold Zoji-la, which they took after dismantling some tanks, hauling the turrets up the mountain, and using them to blast the Pakistanis out of their position (the brigade commander was inspired by his time in Burma busting Japanese bunkers). Through November, the 77th Brigade advanced northeast through the valley, eliminating Pakistani positions one by one. Kargil was taken on 23 November. While the Sonamarg and Srinagar valleys were being cleared out, Carippa sent 5 Brigade up the valley with the goal of linking up with the garrison at Punch, which it accomplished after a grueling three week mountain valley campaign.

At the end of the year, the two sides agreed to a ceasefire, taking effect on 1 January 1949, which froze the lines in place. India kept Pakistani forces out of most of Kashmir and cleared large swaths of the province of Pakistani regulars and irregulars, suffering about 6,000 casualties in the process. Most impressive was the resolve of Indian troops in places like Punch, who held out for months after being encircled. The Indian logistics system, dealing with the sparse roads of Kashmir, not to mention strongholds like the aforementioned Punch, also performed well. Overall, the Kashmir operation was a good first campaign for a new army serving a nation with an uncertain future.

The 1965 War

The 1948 treaty did not bring an end to the Kashmir issue. Pakistan seethed that a Muslim state was part of India, while India insisted that the maharajah had legally acceded to the Indian Union. Internally, Pakistan was a mess. Pakistan had failed to institute land reforms and large tracks of land were held by feudal landlords. The bureaucracy was inefficient and corrupt. Ali Jinnah’s old Muslim League agitated for direct government action to free Kashmir and even called for a coup to replace the government should it refuse to do so. Worse, Punjab was racked by religious violence which the government was unable to bring to an end. The one institution that seemed to work was the army which, under the leadership of General Ayub Khan, expanded and established several branch schools, armor, artillery, etc. In October of 1958, with martial law in effect, Khan took the office of presidency in a move of questionable legality.

From Kahn’s point of view, a war against India had much to offer. A war would rally the nation and distract from Pakistan’s internal problems. Freeing Kashmir would make Khan a national hero and solidify his position as president. Since the drubbing received at the hands of the Chinese in 1962, the Indian army appeared weak and indecisive. Why not go to war? Khan and the army hatched an interesting and complicated plan. First Indian forces were to be drawn away from Kashmir via a border skirmish in the Rann of Kutch, a disputed desert area well to the south of Kashmir. Then a paramilitary force would enter Kashmir and foment a revolt. Lastly, Pakistani forces would invade Kashmir to help quell the disturbances.

The first phase, the Rann of Kutch Operation began in April of 1965 when a Pakistani paramilitary unit, the Indus Rangers, crossed the border and occupied a small village. This effort was joined by elements of a Pakistani infantry brigade which shelled and brought under fire Indian border posts. Then, on the night of 21 April, elements of Pakistani 8th Infantry Division crossed the border. Several clashes between this division and Indian 31st and 50th Paratrooper Brigades (both of which had been sent to the area following the first incursion) ensued. There were several small actions and skirmishes until a ceasefire was agreed upon on 1 May.

From the Pakistani point of view, the first phase of the operation was a success. The ceasefire did not call for a Pakistani withdrawal, indicating that the Indians would accept occupation of their territory. It was time for the second phase of the plan. Pakistani regulars could not outwardly be seen in the opening phases of the operation; therefore a paramilitary force was raised, trained, and equipped. Gibraltar Force, as it was called, was divided into 10 units each of 6 companies of about 110 men. The entire force numbered as many as 60,000 men. The companies were named after great Muslim warriors of the past. Gibraltar Force was led by Major General Akthar Hussain Malik, a veteran division commander.

Phase two of the operation began in early August. The main strike group, Saladin Force, entered Kashmir on 8 August with the goal of wrecking havoc in the all important Srinagar Valley. Other groups attacked targets around Punch, Jhangar, and Chamb among other locations. While the guerillas created countless disturbances in the state, severing roads, blowing up bridges, attacking police stations, they failed to raise the hoped for revolt. As such, Indian 91 and 68 Brigades were free to engage Gibraltar Force without having to worry about the populace. By the end of the month, most of the Pakistani gains had been erased by the Indian army.

Despite the failure of the first phase of the operation, Ayub Khan decided to launch phase three, called Operation Grand Slam. The goal of the attack was to capture Bridgeat Aknur, a village about 40 miles east of the border. Doing so would cut Indian communications with Jammu. The offensive began on 1 September and caught the Indians by surprise. Pakistani 7 Infantry Division reinforced with a pair of armored regiments, attacked from the vicinity of Bhimber, overran Indian border posts, occupied the town of Chamb, and advanced to the Tawi River. But rather than push on, the Pakistanis stopped here allowing the Indians to move reinforcements to the Tawi River line. When Pakistani 7 Infantry Division finally renewed its attack on 5 October, it was confronted by two Indian brigades (plus a frontier battalion) and the drive came to nothing. Worse, the Indian government now led by Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, authorized a general counterattack not only in Jammu but to the south as well. A two pronged offensive begun on 6 September.

The Indian drive on Sialkot

In Jammu, the Indian I Corps crossed the border with the goal of engaging Pakistani forces and taking Chawindra, which would take pressure off of Kashmir. I Corps was centered on Indian 1 Armored Division supported by 14 and 26 Infantry Divisions and 6 Mountain Division. I Corps advanced on a three division front with 14 and 26 Infantry Divisions securing the flanks while 1 Armored Division drove on Chawindra. Indian 1 Armored Division encountered stiff resistance before Chawindra at the village of Phillora, which had to be cleared via brigade level attack. The advance resumed and by 14 September Indian 1 Armored Division was positioned for an attack on Chawindra proper. Pakistani forces defending Chawindra (three armored and three infantry battalions from various brigades) held Indian 1 Armored Division at bay for two days. On the third day, Indian 6 Infantry Division moved southwest and joined the attack. The Pakistanis repulsed this effort as well. On 20 September, several local counterattacks on the part of Pakistani forces sapped Indian strength further. Though almost 500 square miles of territory had been taken, Indian I Corps was unable to seize its objective.

The Indian Drive on Lahore

In Punjab, Indian XI Corps was tasked with advancing to the Ichhogil Canal and establishing bridgeheads on the west bank, thus threatening Lahore. By doing so, they hoped to force a major battle with the Pakistani Army. Each of the corps’ three divisions was hastily scrambled out of barracks and rushed to the border. As such, each was missing a brigade. The risk paid off though as the offensive in Punjab achieved complete surprise. That said, there was dogged fighting with Pakistani border rangers as well as Pakistani 11 Division which was screening Lahore.

The Indians advanced on a three division front. In the North, Indian 15 Division, advancing along the Grand Trunk Road, crossed the border and made for the bridge at Dograi, which the Pakistanis had damaged but not enough to drop it into the water. Indian troops secured the bridge and walked across the canal under fire. However, as Pakistani forces counterattacked, Indian troops on the west bank pulled back to the east bank. To the north, Indian 38 Brigade was charged with clearing Pakistani positions south of the Grand Trunk Road, but met stiff resistance and was unable to advance. Further attacks by Indian 38 and 54 Brigades along the canal were stopped. Indian 50 Para Brigade was brought in and finally broke through Pakistani defenses and occupied positions on the west bank. In the center, Indian 7 Division fought several battles for a trio of Pakistani villages just west of the canal. Once these were cleared, the town of Bakri, which had been fortified with ten pill boxes, was taken against heavy resistance. A further push to the south was stopped by Pakistani forces.

In the south, Indian 4 Mountain Division was tasked with occupying the east bank of the canal and taking up positions in the Sutlej River. The division’s advance was going well until 8 September when the Pakistanis launched a major armored counterattack. The effort consisted of Pakistani 1 Armored Division supported by their 11 Infantry Division. Contact was first made in the early morning. Upon spotting the tanks, the lead elements of Indian 62 Brigade fell back, some battalions fled. The Pakistanis had achieved a minor breakthrough. But rather than exploit their advantage, they waited until the next day to resume the advance. By then, Indian reinforcements had been brought up. There ensued a two day tank battle in the vicinity of Kehm Karan in which Pakistanis tried to break through Indian defenses but to no avail. In the fighting, they lost 97 tanks.

The war ended on 23 September. Strategically, it was a loss for Pakistan. The plan to seize Kashmir failed. Once India beat back the attempt on Kashmir, they seized the initiative and invaded Pakistan. Each thrust lacked purpose and seemed orchestrated simply to engage the Pakistani army. After all, what would India want with Lahore or Armritsar? That said, Indian troops performed well, exacting a heavy toll on Pakistani armored units whose commanders, when they weren’t being too cautious, were charging blindly into the teeth of Indian guns. After the humiliation of the Chinese war, the 1965 War was a relief and a victory for India.

The 1971 War

A great challenge loomed in 1971. Since independence Pakistan’s fatal flaw was that it was divided into two spheres, East and West Pakistan, separated by over a thousand miles with India in between. With the capital, government agencies, and army headquarters all located in West Pakistan, and most government funds spent in the west, by the 1960s, the people of East Pakistan (or East Bengal) came to feel that they were little more than a neglected colony of West Pakistan. East Bengal’s Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, agitated for greater independence from the west. In the national assembly elections of 1970, the Awami League won an absolute majority. Rather than accept the new reality, Yahya Khan, Pakistan’s president, refused to call the assembly to session and launched a brutal crackdown in East Bengal.

A bloodbath ensued. Pakistani army units battled protestors in the streets, fired indiscriminately into crowds and targeted East Bengali leaders. The Awami League was outlawed, Sheikh Rehman was arrested and much of East Bengal’s educated class was liquidated. University campuses were leveled and TV and radio stationed seized. Mass communal rape became the policy of the Pakistani army. Bengali units of the Pakistani army mutinied and fought their former comrades. Hundreds of thousands were killed as civil war raged across the country and millions fled to India.

In New Delhi, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (Nehru’s daughter) convened an emergency cabinet meeting and demanded the army make preparations for an immediate invasion of East Bengal. The chief of staff, General Sam Manekshaw, flat out refused to do so and offered to resign. He told the cabinet that his forces were unprepared for an invasion that he had only one division in the region and this was not enough to achieve victory in East Bengal. Worse, the vast majority of tanks in the Indian 1st Armored Division were inoperable. When the finance minister asked Manekshaw why this was so, the general replied, ‘Because you are finance minister.’ East Bengal, Manekshaw explained, is a low lying country crossed by several waterways, some of them miles wide. In order to liberate the country, Manekshaw told the cabinet he needed time, time to gather sufficient force –in this case several divisions - time to find bailey bridges, time to gather proper artillery for his infantry and mountain divisions, time to train and arm Bengali insurgents and time to plan the invasion. A visibly angry Gandhi yielded to Manekshaw who was given cart-blanche to plan and carryout the invasion.

The next months saw a flurry of activity on the part of the Indian army and its general staff. Eastern Command, led by General Singh Arora, would be responsible for the invasion of East Bengal. Several mountain divisions, oriented north, were redeployed to the border with East Bengal. Artillery had to be found for these divisions as well. World War Two era bailey bridges were located in various depots in India and sent to the front. Supply depots were established around East Bengal; 4,000 tons were put in depot at Raigarh, 7,000 at Taigarh, and 14,000 at Krishnanagar. Eastern Command’s staff was reorganized and liaisons established with the navy and air force, both of which established special commands in Calcutta. Planning the invasion fell to General JFR Jacob, Eastern Command’s Chief of Staff. Under his direction, the final plan called for the avoidance of Pakistani strongpoints. Instead, Indian forces would cross the border en masse, draw Pakistani reserves forward and bypass their strong points, making instead for communication hubs in the rear. The ultimate goal was the Dacca Bowl.

While India was gathering its strength, Pakistan was preparing to defend East Bengal. General A.A.K. Niazi, commander of Pakistani forces in East Bengal, was ordered by the government to conduct a forward defense and prevent Indian forces from gaining a toe hold in Pakistani territory. Yahya Kahn was concerned that any such gains would be declared ‘Free Bengal’. A far better strategy would have been to fall back to the Dhaka Bowl, a geographic feature in the center of the country formed by the wide and deep Meghna and Jamuna rivers. Crossing these rivers would have been a formidable task for Indian army units. In any event, Niazi had four and half divisions deployed throughout Pakistan. As they had months to prepare for the invasion, Pakistani forces built fortifications throughout the country, turning many villages and towns into fortresses. Once the war began though, these fortified areas became death traps as Pakistani movement was extremely hampered due to Indian air superiority and the fierce hostility of the Bengalis. The local resistance movement, the Mukti Bahini, harassed Pakistani troops throughout the country, and more importantly, reported troop movements to Indian intelligence.

In late November, Indian forces advanced a few miles into East Bengal in preparation for the main assault. The war did not begin until 3 December and was actually initiated by Pakistan. That night Pakistani jets bombed Indian airbases all along the western border with India. Pakistani planners had hoped to save East Bengal by winning a decisive victory on the western front. Their opening blow failed miserably. Meant to emulate the Israeli preemptive strike in 1967, the Pakistani effort scored few direct hits on Indian airfields and did not destroy a single aircraft.

Jacob’s plan divided East Bengal into several sectors, East, North, and West. Fighting in East Bengal followed a general pattern throughout. Pakistani forces offered stubborn resistance on the border and then withdrew to fortified towns in the interior. Despite General Jacob’s warning to avoid these areas, Indian forces expended much time and energy in fruitless assaults on towns such as Hilli and Jessore. Because Pakistani forces were pinned by the attacks, Indian forces were able to work around their flanks and get behind them, pushing to the Meghna and later the Jammu.

An ad-hoc force of four independent brigades was gathered on East Bengal’s northern border. Advancing without having to cross a major river, this force made good progress through the course of the war. A Pakistani force held out in Jamalpur, which was surrounded and finally surrendered on 11 December. The advance was also aided by an airborne drop against Madhupur and Mymensingh, where the timely drop of a reinforced airborne company exacted a heavy toll from Pakistani troops withdrawing from Mymensingh. Helicopter-borne troops were also deployed at Tangil an important town on the road to Dacca. The advance was so successful that, by 13 December, two Indian brigades and an airborne battalion were just outside of the Bengali capital.

The Indian advance in the east also went well. Their goal was to knock Pakistani forces off the border, drive to the Meghna and force a crossing. The job fell to IV Corps which advanced on a two division front. On IV Corps’ northern flank, Indian 57 Division cleared Pakistani troops out of several towns and was on the banks of the Meghna by 9 December. The next two days were spent building bridges across the river, which was crossed on 12 December. With the Dacca Bowl breached, the advance resumed and by the night of 14 December, Indian 57 Infantry Division was 20 miles from Dacca proper. To the south, Indian 23 Infantry Division had a tougher fight. After crossing the border, they enveloped Pakistani forces in the town of Laksham and pushed on to Mudafarganj, which they took. After repelling several brigade level counterattacks the division drove on Chadpur and took it on 8 December. On orders from General Manekshaw an ad-hoc unit, named Kilo Force, was created from elements of 23 Infantry Division and the Mukti Bahini. Kilo Force advanced southeast toward Chittagong, East Bengal’s second city, reaching its outskirts by the night of 14-15 December.

In the west, the Indians advanced on a two pronged front. On the Indian left, XXXIII Corps was to clear out the northwest part of the country and establish itself on the Jammu River. Indian 6 Mountain Division crossed the border and seized a pair of towns north of Rangpur. Indian 20 Infantry Division’s advance was stopped by Pakistani forces occupying the town of Hilli. Despite Jacob’s intention to avoid such a fight, 20 Infantry Division tried for four days to overcome Pakistani defenders there, but still were only able to occupy it when Pakistani forces pulled out. Indian 20 Infantry Division then advanced to the River Jamuna and took the town of Bogra, a communications hub vital to Pakistani forces still defending the border area. On the Indian right, II Corps was to secure a bridgehead for a possible drive on Dacca. Indian 4 Mountain Division engaged Pakistani forces in several stiff fights, first for Kushtia, then to the east at Faridpor. Further south, Indian 9 Infantry Division sized Jessore and then engaged and destroyed Pakistani brigade to the west in the vicinity of Khulna but became bogged down before the town and was unable to advance further.

The End of East Pakistan

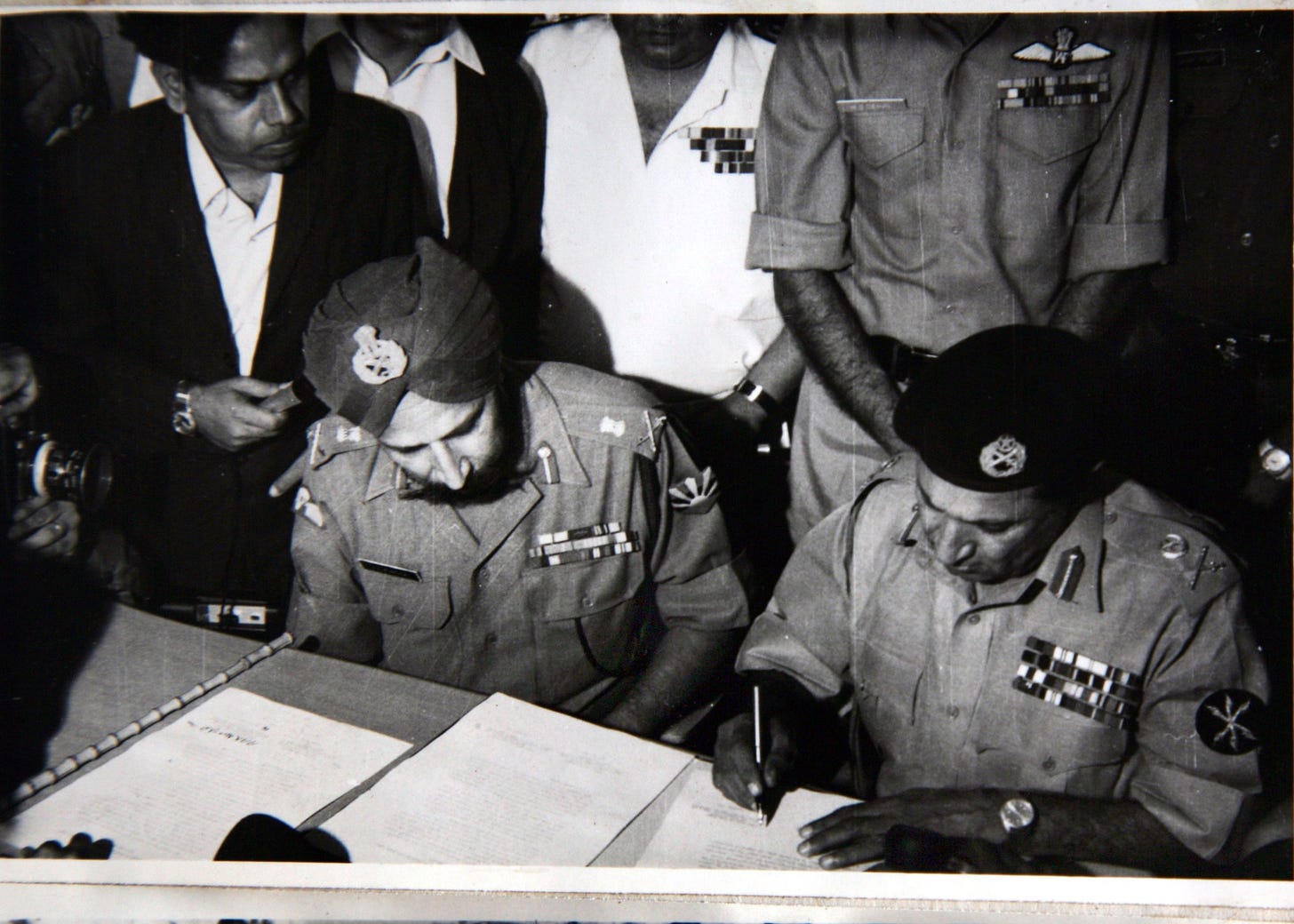

General Jacob’s plan was a success. By 15 December, Indian forces were closing in on Dacca from the north, across the Meghna, and into the Dacca Bowl in the east. In West Pakistan, the offensive there, launched against Indian forces at Chamb in the north, Jaisimlar in the center, and Punjab in the south, was a complete failure. Pakistani units failed to breach Indian defenses and, in some cases, were humiliated. At the battle of Longawela, Pakistani 22 Cavalry Regiment was stopped by a company of Indian infantry and then pounded from the air by Indian Hawker Hunters, who destroyed 17 tanks and 23 other vehicles in an afternoon turkey shoot. With no hope of salvation in the west, General Niazi had no choice but to capitulate. On 16 December, Niazi signed a formal instrument of surrender, sending himself and 93,000 Pakistani soldiers into captivity.